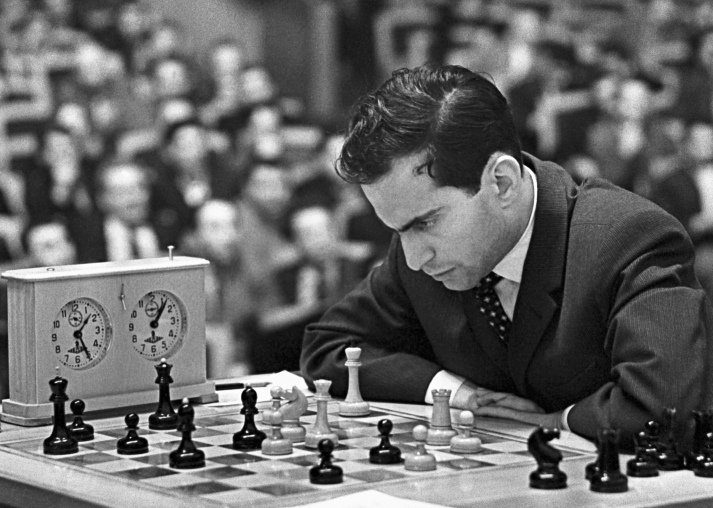

Mikhail Tal lived for, breathed, and spun magic in chess. The most creative attacking player who ever graced the planet, Mikhail Nekhemevich Tal is a name that brings with it a poignant reflection: a chess genius who burnt himself out too quickly like a blazing candle in the wind.

The 8th World Champion, Tal was one of the most aggressively attacking players to grace the title. At the age of 13, Tal played for his native Latvia youth team. He won the Latvian championship when he was 17. By the age of 21, he would win the USSR championship.

Mikhail Tal rose to fame and glory in the late 1950s. Young and fierce, Tal won the Soviet Chess Championship successively in 1957 and 1958. In 1960, Mikhail Tal became the then-youngest World Chess Champion, winning the crowns at the Interzonal Tournament and the Candidates Tournament in 1958 and ’59 respectively.

In his career, Mikhail Tal won five International Chess Tournaments. He held the record of winning the Soviet Championship six times. Tal represented the Soviet Union eight times on Olympiad teams and won the team gold on all eight occasions. He also participated in six Candidates Tournaments.

The Politics of Being Mikhail Tal

The young and adventurous ‘Misha’ - as he was called - seemingly breached all prevalent rules of the game, basking in the awe and adoration of a huge fan base.

Chess was everything for Tal. He cast his magic with his games and lived for it. Everything else – money, luxury, or politics - never bothered him. He was indifferent to life’s trivia and sidelined them: including daily routine and domestic life. “Misha” was regularly late for flights, would wear two different shoes for days and never notice the difference, forget about a prize worth thousands or just lose a large sum of money.

Living in the then Soviet Republic, he was seldom bothered by the political realities. Unlike his compatriots like Botvinnik, Petrosyan, Smyslov, and Karpov who explicitly displayed their communist loyalties and received favor from the authorities, Tal found the political affairs a hindrance that must be evaded. Tal was never anti-Soviet, he was beyond noticing the shortcomings of a system that seemed to ignite other contemporaries like Spassky. While Spassky was a rebel with a sharp tongue against the Soviet government, Tal was alien to all these considerations.

Anything that seemed to block his stream of ‘chess’ consciousness was bluntly removed, just like the pawn in one of the Olympiads. When a surprised Michael Botvinnik enquired about a pawn that Tal gave up – for no particular benefit – Misha’s answer was “It disturbed me.”

Strength amidst Sickness

Though he remained strong in his game in the successive decades, Tal’s long-standing smoking habits and varied illnesses began taking a toll on his health. He was a chain-smoker, was not a stranger to alcohol, and refrained from any other physical sport.

In 1960 he lost his championship title to his compatriot and namesake Mikhail Botvinnik. In the 1962 Candidates Tournament, he spent three-quarters of the qualifying tournament on pills, only to end up in hospital.

Though chronic illnesses strangled his career Tal played on – until death beckoned him in 1992. Tal was also known for his cheeky humor – something that kept him going amidst persistent ill health. Unlike his predecessors Paul Morphy who got deranged during his final years or Capablanca who suffered from extreme hypertension that turned fatal, Tal pulled himself through life’s melodrama with a cheerful spirit.

Perhaps it must have been his amazing sense of humor that helped him climb out of the miry pit of illnesses and get back to the game. His comments, observations, and responses were liberally salted with pun and wit.

During the late sixties, Tal’s health deteriorated badly. Major newspapers even kept obituaries ready for the young magician from Riga who was barely thirty. Misha got back to his feet and back on to the track by 1964, as his health improved. He tied for first in the Interzonal, with a score of +11 and devoid of a single loss. Though he beat Portis and Larsen on his way to the world championship, he lost to Spassky in the final Candidates match. Tal became the official rank-3 player in the world.

In 1966, the Olympiad in Havana too turned tragic for Tal. A bottle from an anonymous source hit his head in a bar and had him sent to the hospital. Though confined to bed for a few days, Tal bounced back with his aggressive strike at his opponents. As Tigran Petrosian remarked, "only Tal with his cast-iron health could come round so quickly".

In 1968, Mikhail Tal lost to Kortchnoi and crashed out of the world championship cycle. Not only did Tal make it to the Olympic team, but he was also ‘replaced’ on the previous day of the departure by an older and lesser ranked Smyslov. Smyslov had no better ground than Tal to be a part of the delegate but Tal was clearly not the authorities’ darling.

The 7 Most Controversial Chess Championships in History

The Maestro of Fantasy

Tal was incredibly good against players who were strong enough but less skilled than himself. He was brilliant in psychologically intimidating his opponents: getting them confused, stumbling into time trouble and making mistakes. Much like Capablanca and Fischer, Tal was a player opponents were scared of. With a dare-devil attitude he never hesitated to even sacrifice pieces to gain a thrilling breakthrough.

However, cracking opponents – world champions - who were of his level, as well as strong counter punchers like William Stein, Victor Korchnoi, or Lev Polugayevsky – was a tough nut for Tal.

He would soar high on creativity, but harsh reality often brought him and a few pieces down. His style worked well when he was in his best spirit and health, but turned disastrous when he wasn’t suffering physically or emotionally.

In the late sixties and early seventies, Tal experimented with his game style but in vain. In the USSR Championship 1970, held in his native place Riga, he was even denied entry.

Though he managed to catch up with his old glory during 1972-1973, his destructive ill-health backlashed, leaving him devastated at the most significant tournament of the year, the Interzonal in Leningrad (1973).

The next year Tal won the USSR Championship, sharing the title with the young Alexander Belyavsky, but sadly, the spark that kindled the Magician from Riga was long gone.

In the following years, Tal failed to qualify for the Candidates. An almost forty Tal had track marks all over his arms. His peers teased him over apparent “morphinism”.

With Karpov: The resurrection

Tal’s turning point came in the form of helping Anatoly Karpov in his duel with Victor Korchnoi who defected to the Netherlands in 1976. Tal was assigned to mentor the Soviet champion - who was a favourite of the authorities – in the battle against the renegade.

For Mikhail Nekhemevich Tal, the ideological differences rarely mattered. As long as the game was chess, he played along. Tal worked hard for the first time in his life, helping Karpov. Assisting the champion of chess - his complete antithesis – brought in a new wave of energy and discipline for Tal. He became subdued with a far more practical, composed and rooted approach to the game.

With renewed energy, Tal won a series of events from the USSR Championship in 1978, the Montreal super tournament (1979) (with Karpov), to the Interzonal in Riga (1979). He also achieved a spectacular rating of 2705, ranking third after Fisher and Karpov.

However, the Candidates match against Lev Polugaevsky in 1980 proved to be his nemesis. A face-off with Polugaevsky, the world's best debut analyst on his territory, was a reckless decision. Though a confident Tal prepared well and had the back-up of Alvis Vitolins - the brightest analysts of that time - Polugaevsky won.

The Final Glow

Though the magic of Mikhail Tal plummeted, it never fizzled out. He consoled and often enthralled his fans for another 12 years with cherishable performances.

He had remarkable success in the Interzonal in Tasco (1985), an incredible victory at the first World Blitz Championship 1988, and good results in the Candidates. His games often ended in a draw after one hour of play; he tasted a different chess and set his record against Korchnoi right.

But the fire that was Mikhail Tal was fast fading. His long-standing illnesses were slowly consuming him. Even through his struggling fifties, Tal maintained the highest level and contributed to the sport that he breathed through numerous articles, performances and chess coaching sessions for kids. Till his end in 1992, Misha stayed true to his passion.

The suave, charming, and highly educated lady's man was just 56 years old as he bid adieu to the world and his passion. The fierce and fearless warrior left a void in creative chess that only his magic could fill.